When we think of the internet, we usually imagine a borderless, decentralised cloud, a digital utopia where information flows freely, connecting the whole of humanity. But this image is a comforting illusion. In reality, the internet is a physical, political, and economic entity. It has a geography, and that geography is starting to look unsettingly familiar.

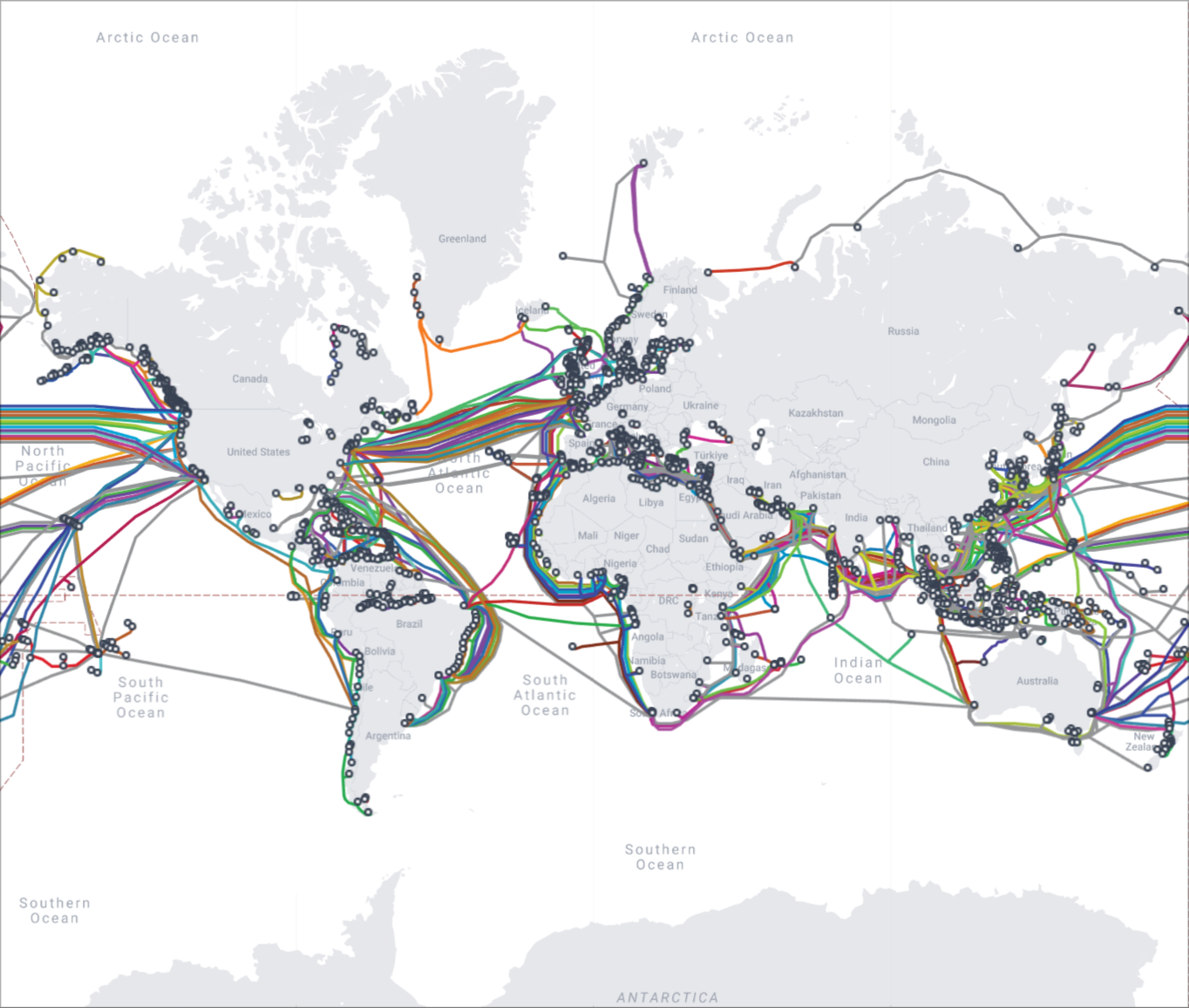

Beneath the oceans lie the true arteries of the digital world, a sprawling network of submarine fiber-optic cables. Look at a map of these cables, and you’ll see the faint outlines of 19th-century shipping routes. These modern data highways, much like the trade routes are not built for universal connected but for strategic advantage. They connect powerful economic hubs in the Global North, while often bypassing or merely extracting from the Global South.

Courtesy: TeleGeography

Courtesy: TeleGeography

This is the foundation of a new kind of global power dynamic, a “New Colonialism” where the tools are not gunships and railroads, but fiber-optic cables and data centres. Tech companies, once seen as disruptive innovators, are becoming the new colonial powers, redrawing the world’s borders with infrastructure, data and algorithms.

Cable Colonialism - The New Shipping Routes

In the 19th century, colonial empires were build on the control of the seas. Whoever owned the shipping lanes controller the flow of good, wealth and consequently power. Today, the same logic applies, but the commodity has changed. The most valuable resource in the 21st century is data, it flows through cables owned and dominated by a handful of corporate giants.

Companies like Google and Meta are no longer just users of this infrastructure; they are its primary builders and owners. They are laying their own private submarine cables, creating proprietary networks that prioritise their own data traffic. For example, Google’s “Equiano” cable runs from Portugal down the West African coast, and Meta’s “2Africa” project is creating a massive ring around the continent.

On the surface, this seems like a beneficent investment, bringing connectivity to underserved regions. But it creates a new form of dependency. These cables are not public utilities; they are private assets. The decisions about where they land, who gets access and at what price are made in corporate boardrooms in California, not by the nations they connect. This mirrors the colonial model where infrastructure was built not for the benefit of the local population, but to facilitate the extraction of resources back to the imperial core.

Data - The New Raw Material

If cables are the new shipping routes, then data is the new raw material. Colonial powers extract cotton, rubber, and minerals from their territories, shipped them to the metropole for processing and sold finished good back to the colonies. Today, a similar process is happening with data.

Every click, like, search, and location ping from a user in Africa, Southeast Asia, or Latin America is a raw resource. This data is harvested and transported through the submarine cables to massive data centres located almost exclusively in the Global North - the United States, Europe, and increasingly China. Here, it is refined using sophisticated machine learning algorithms into valuable products; targeted advertising profiles, AI models and market insights.

The value is not in the raw data itself, but in its processing. An African user’s data is processed in a European data centre by an American company, to train an AI that will be licensed and sold globally. The wealth and intellectual property are generated far from the data’s source. This is “Data Extractivism” a one-way flow of value that preserves economic inequality. The digital economy, promised as a great equiliser, is instead reinforcing old dependencies.

The Infrastructure Gap

The fragility of this system was laid bare in January 2022, when a volcanic eruption severed the single submarine cable connecting the island nation of Tonga to the rest of the world. The country went dark for over a month, a stark reminder of the vulnerability that comes with being at the periphery of the global network.

This is not an accident, it’s a feature of the current system. While Europe and North America are crisscrossed by a dense mesh of redundant cables, ensuring constant connectivity, entire regions of the world depend on one or two points of failure. This “infrastructure gap” is deliberate and a direct consequence of a market-driven approach to a critical resource. It is not profitable to build redundancy for Tonga in the same way it is for New York or London.

This creates a digital caste system. Those in the well-connected core enjoy a resilient, high-speed internet that is a given, like electricity or running water. Those on the periphery experience a fragile, slower and more expensive version, subject to the whims of geography, economics and even natural disaster. This digital divide is no longer just about access to a computer; it’s about the quality and reliability of the very fabric of connection.

Languages and Algorithms Bias

The new colonialism extends beyond physical infrastructure and into the code itself. The algorithms that shape our digital experience; from search results to mapping applications are on data that is overwhelmingly Western in origin and perspective.

When a mapping algorithm prioritises English place names over indigenous ones, it is making a political statement. When a natural language processing model performs flawlessly in English but struggles with Quechua or Swahili, it reinforces linguistic hierarchies. This is not a technical limitation; it is a reflection of the data used to train these systems. If the training data is sourced primarily from the Global North, the resulting models will see the world through a Western lens.

This “Algorithmic gaze” subtly shapes our understanding of the world, centring one perspective and marginalising others. It is a form of cultural dominance, less obvious than a missionary imposing a new religion, but perhaps more pervasive. It determines what is visible, what is important and what is “standard”.

The Counter-Revolution - Digital Sovereignty

In response to this new paradigm, nations are beginning to push back. The dream of a single, global internet is fracturing, and digital borders are being erected. The is a battle for “Digital sovereignty”.

China’s “Great Firewall” is the most well known example, a state controller intranet designed to insulate its population from the Western-dominated internet. Russia has pursued similar policies, testing its ability to disconnect from the global web entirely.

But the push for digital borders is not limited to authoritarian regimes. The European Union through regulations like the GDPR, has asserted its own form of digital sovereignty. Its data localisation laws, which require companies to store and process European citizens’ data within EU, are a direct challenge to the extractivist model. They are an attempt to build a “walled garden” to protect their citizens’ data from the reach of American tech giants and government surveillance.

These movements, while diverse in their motives, all stem from the same realisation; in the 21st century, controller your digital territory is as important as controlling your physical territory.

The Map of the Future

The promise of a border less digital world was a powerful one, but it was naive. It ignored the fundamental forces of economics, politics, and power that have always shaped our world. The internet is not a cloud; it is a network or cables, data centres, and algorithms, owned and controlled by powerful actors with their own interests.

We are in the early days of this new colonial era. The territories are digital, the resources are informational, and the power is algorithmic. The result is a redrawing of the world map, with new centres of power, new peripheries of dependence, and new battles for sovereignty.

Understanding this new geography is the first step towards navigating it. What does it mean to be a citizen of a digitally colonised nation? How can we advocate for a more equitable and decentralised internet, one that fulfils the original promise of connection rather than reinforcing old hierarchies? The borders are being drawn now. The important question is, who gets to hold the pen?